STANDARD 5

OVERVIEW

- Individuals with OA often experience weakness in lower extremities which may lead to functional and mobility decline over time – a sedentary lifestyle is a major risk factor of OA as it aggravates symptoms

- Regular exercise and physical activity should be built into a care plan using shared decision making to select treatments that suit the goals and baseline fitness of the individual

- Most recommended exercises and physical activities for hip and knee OA target lower extremities, including trunk/core, gluteal, quadriceps, hamstring, and calf muscles

- Prescribed movement can be suggested as independent work, or as a part of joining structured programs, and when safe the individual can gradually progress the intensity, frequency, and duration over time

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip or knee often experience weakness in their lower extremities1,21de Zwart AH, Dekker J, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Van Der Esch M, Van Der Leeden M. Factors associated with upper leg muscle strength in knee osteoarthritis: A scoping review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2018;50(2):140-50.

2Øiestad BE, Juhl CB, Eitzen I, Thorlund JB. Knee extensor muscle weakness is a risk factor for development of knee osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2015;23(2):171-7. which, combined with poor neuromuscular function, may lead to functional and mobility decline over time. A sedentary lifestyle is one of the major risk factors of OA as it aggravates symptoms and contributes to a lower quality of life.33Musumeci G, Aiello FC, Szychlinska MA, Di Rosa M, Castrogiovanni P, Mobasheri A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst century: Risk factors and behaviours that influence disease onset and progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(3):6093-112. Physical deconditioning due to inactivity not only exacerbates symptoms but can also negatively impact overall health.1,41de Zwart AH, Dekker J, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Van Der Esch M, Van Der Leeden M. Factors associated with upper leg muscle strength in knee osteoarthritis: A scoping review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2018;50(2):140-50.

4Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

Regular exercise and physical activity are among the most effective conservative treatments to improve symptoms and maintain physical fitness in people with OA of the hip or knee.4,54Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

5Rice D, McNair P, Huysmans E, Letzen J, Finan P. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 5: Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019;8(11):1769. Exercise and physical activity are related but not equal and have a variety of benefits and components (see below).

Self-management strategies (Standard 3) should be discussed in conjunction with introduction of exercise prescription and physical activity programs. If the individual with OA gains confidence in understanding their body and options for modifying their exercises and physical activities, they will be better able to safely exercise and carry out their day-to-day activities.

Understanding Prescribed Exercise vs. Physical Activity

Prescribed Exercise

Physical Activity

- Purposeful movements

- Targeted to specific body parts

- Structured movements

- Repetitive movements

- Any leisurely action or task performed in everyday environments

- Encourages movement of all body parts

- For improving overall health and wellness

- No structure

- Not targeted

- Not purposefully repetitive

- 6 week arthritis pool therapy program

- GLA:D® program

- Gardening

- Walking to the store

- Helps reduce OA symptoms including severity of pain and mobility restrictions

- Reduce medication dependency

- Improve mental health and cognitive function

- Protects joints from further deterioration

- Weight bearing exercise can significantly improve the health of the cartilage of the affected joint

- Some structured programs will allow for individual self-referral

- Self-select and self-modify readily

- Education on safe practices

- Steps for improving levels of exercise and physical activity

- Support to lead an active lifestyle

- Education to understanding the specific exercises and why they were chosen

- Education on how physical activity impacts joint pain, particularly impact vs. non-impact

- Range of motion

- Targeted muscle strengthening

- Neuromuscular training

- Aerobic exercises

- Activities that help to increase heart rate and level of exertion. This can include:

- Moderate activities

- Vigorous activities when safe to do so.

PRESCRIBING MOVEMENT

During care planning with an individual, the Primary Clinician should offer options for exercise and physical activity to address strength and flexibility, in balance with cardiovascular fitness. Alternatively, depending on the scope of the Primary Clinician’s expertise, they can refer to other clinicians, in particular those qualified and experienced in prescribed exercise to develop a targeted exercise program. Most recommended exercises and physical activities for hip and knee OA target lower extremities, including trunk/core, gluteal, quadriceps, hamstring, and calf muscles.

It is important to use shared decision-making techniques to build movement into a care plan. If the individual is choosing exercise and activity they are interested in, they will be more likely to enjoy and complete them. A well-rounded movement plan:4,64Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

6Holden MA, Button K, Collins NJ, Henrotin Y, Hinman RS, Larsen JB, et al. Guidance for implementing best practice therapeutic exercise for people with knee and hip osteoarthritis: what does the current evidence base tell us? Arthritis Care & Research. 2020;Accepted for publication.

- Accommodates for the individual’s baseline wellness;

- Addresses the individual’s:

- Needs

- Goals

- Symptoms

- Socioeconomic status

- Preferences and

- Values

- Has a preliminary plan for progression

- Collects outcome measures

- And incorporates:

- Daily movement goals (see below)

- Education on safe practices:

- Recovery strategies

- Pain tracking and managing strategies

- Pacing and modification strategies and

- Strategies to improve motivation to maintain an active lifestyle

Prescribed movement can be suggested as independent work for the individual or as part of joining structured programs. The Tables of Examples for the Conservative OA Treatments provides a variety of categorized examples of independent or structured programs. Structured programs may be offered on-site or virtually, with individual supervision or in a group setting. Note that structured programs may incur costs. The individual’s socioeconomic status should be considered before selecting treatment options.

Over time, work with the individual with OA to safely and gradually progress the intensity, frequency and duration of an exercise or physical activity. Build relationships with the community-based exercise program providers in the area to ensure individuals with OA are directed to the program that is most applicable to their needs.

Movement Target

With clinician approval for medical safety a target of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic movement per week is recommended7,87Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; 2021 [Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/].

8World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Geneva; 2020. .

INTRODUCTION

2Øiestad BE, Juhl CB, Eitzen I, Thorlund JB. Knee extensor muscle weakness is a risk factor for development of knee osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2015;23(2):171-7. which, combined with poor neuromuscular function, may lead to functional and mobility decline over time. A sedentary lifestyle is one of the major risk factors of OA as it aggravates symptoms and contributes to a lower quality of life.33Musumeci G, Aiello FC, Szychlinska MA, Di Rosa M, Castrogiovanni P, Mobasheri A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst century: Risk factors and behaviours that influence disease onset and progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(3):6093-112. Physical deconditioning due to inactivity not only exacerbates symptoms but can also negatively impact overall health.1,41de Zwart AH, Dekker J, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Van Der Esch M, Van Der Leeden M. Factors associated with upper leg muscle strength in knee osteoarthritis: A scoping review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2018;50(2):140-50.

4Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

Regular exercise and physical activity are among the most effective conservative treatments to improve symptoms and maintain physical fitness in people with OA of the hip or knee.4,54Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

5Rice D, McNair P, Huysmans E, Letzen J, Finan P. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 5: Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019;8(11):1769. Exercise and physical activity are related but not equal and have a variety of benefits and components (see below).

Self-management strategies (Standard 3) should be discussed in conjunction with introduction of exercise prescription and physical activity programs. If the individual with OA gains confidence in understanding their body and options for modifying their exercises and physical activities, they will be better able to safely exercise and carry out their day-to-day activities.

Understanding Prescribed Exercise vs. Physical Activity

Prescribed Exercise

Physical Activity

- Purposeful movements

- Targeted to specific body parts

- Structured movements

- Repetitive movements

- Any leisurely action or task performed in everyday environments

- Encourages movement of all body parts

- For improving overall health and wellness

- No structure

- Not targeted

- Not purposefully repetitive

- 6 week arthritis pool therapy program

- GLA:D® program

- Gardening

- Walking to the store

- Helps reduce OA symptoms including severity of pain and mobility restrictions

- Reduce medication dependency

- Improve mental health and cognitive function

- Protects joints from further deterioration

- Weight bearing exercise can significantly improve the health of the cartilage of the affected joint

- Some structured programs will allow for individual self-referral

- Self-select and self-modify readily

- Education on safe practices

- Steps for improving levels of exercise and physical activity

- Support to lead an active lifestyle

- Education to understanding the specific exercises and why they were chosen

- Education on how physical activity impacts joint pain, particularly impact vs. non-impact

- Range of motion

- Targeted muscle strengthening

- Neuromuscular training

- Aerobic exercises

- Activities that help to increase heart rate and level of exertion. This can include:

- Moderate activities

- Vigorous activities when safe to do so.

PRESCRIBING MOVEMENT

It is important to use shared decision-making techniques to build movement into a care plan. If the individual is choosing exercise and activity they are interested in, they will be more likely to enjoy and complete them. A well-rounded movement plan:4,64Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, Duong V, Dziedzic KS, Allen KD, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: Efficacy and models for implementation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16(8):434-47.

6Holden MA, Button K, Collins NJ, Henrotin Y, Hinman RS, Larsen JB, et al. Guidance for implementing best practice therapeutic exercise for people with knee and hip osteoarthritis: what does the current evidence base tell us? Arthritis Care & Research. 2020;Accepted for publication.

- Accommodates for the individual’s baseline wellness;

- Addresses the individual’s:

- Needs

- Goals

- Symptoms

- Socioeconomic status

- Preferences and

- Values

- Has a preliminary plan for progression

- Collects outcome measures

- And incorporates:

- Daily movement goals (see below)

- Education on safe practices:

- Recovery strategies

- Pain tracking and managing strategies

- Pacing and modification strategies and

- Strategies to improve motivation to maintain an active lifestyle

Prescribed movement can be suggested as independent work for the individual or as part of joining structured programs. The Tables of Examples for the Conservative OA Treatments provides a variety of categorized examples of independent or structured programs. Structured programs may be offered on-site or virtually, with individual supervision or in a group setting. Note that structured programs may incur costs. The individual’s socioeconomic status should be considered before selecting treatment options.

Over time, work with the individual with OA to safely and gradually progress the intensity, frequency and duration of an exercise or physical activity. Build relationships with the community-based exercise program providers in the area to ensure individuals with OA are directed to the program that is most applicable to their needs.

Movement Target

With clinician approval for medical safety a target of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic movement per week is recommended7,87Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; 2021 [Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/].

8World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Geneva; 2020. .

Referral Between Clinicians

The following matrix is provided to guide clinicians on referrals and building a multi-disciplinary team of support for an individual with osteoarthritis (OA). Some supporting clinicians will work in a dedicated team at the same centre as a Primary Clinician, other supporting clinicians will work at separate organizations in the community.

| Category of OA Treatments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discipline that may offer the treatment | Education | Exercise and Physical Activity | Weight Management | Supports (Walking and Environmental | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy | Inter-disciplinary Self-Management Programs | Non-prescription Pharma Treatments | Prescription Pharma Treatments | Intra-articular Injections |

| Family Physicians | X | X* | X | X | X* | ||||

| Nurses | X | X | X | X* | |||||

| Physiotherapists | X | X | X | X* | X | Restricted | |||

| Occupational Therapists | X | X | X | X* | X | ||||

| Kinesiologists | X | X | X | ||||||

| Exercise Physiologists | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sport and Exercise Medicine Physicians | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Radiologists | X | ||||||||

| Rheumatologists | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Physiatrists | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Chiropractors | X | ||||||||

| Orthopaedic Surgeons | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Pharmacist | X | X | |||||||

| Registered Dietitians | X | X | |||||||

| Counsellors | X | X | X | ||||||

| Psychiatrists | X | X | X | ||||||

| Psychologists/Mental Health Therapists | X | X | X | ||||||

| Podiatrists | X | X | |||||||

| Pedorthists | X | ||||||||

Note: The method of delivery of conservative OA treatments can vary between disciplines, between practices and between communities. Clinicians should talk with their individual with OA to make sure the referral will be the right fit for the individual.*Note: Clinicians can offer these services with the applicable training.

Components of Prescribed Exercise Programs

Prescribed exercise programs that are designed to target muscles related to supporting the affected hip and knee joint may include:

Range of Motion: Moving the joint to its full range will improve joint health and mobility, muscle action and relaxation. Best performed when muscles and joints are warmed up, i.e. after activity such as walking or cycling.

Targeted Muscle Strengthening: Includes weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises to strengthen the specific muscles supporting the affected joints as well as strengthen the core muscles. This will improve function, balance and reduce the risk of injury. Stronger muscles around your joints can help stabilize the joint and slow changes to the bone and cartilage.

Neuromuscular Training: Coordinated muscle movements to improve strength, balance, agility, neuromuscular control and appropriately apply load on joints.

Aerobic Exercises: Cardiovascular exercises that vary in intensity but performed in longer duration. Over time, it can improve endurance, energy and general physical and mental wellness.

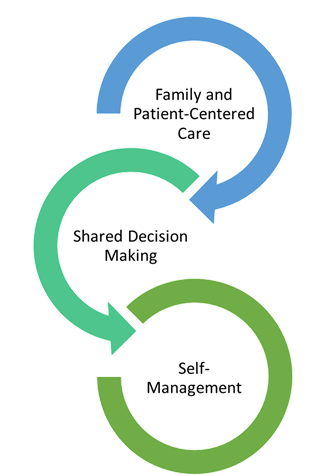

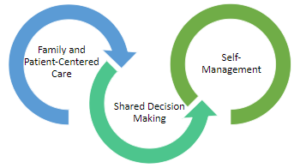

Shared Decision Making

The inter-twining principles that ground the Comprehensive Quality Care Standards for Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee.

Shared decision-making (SDM) techniques and processes are emphasized throughout these standards. The use of SDM is essential to achieving ‘family and patient-centric’ care. SDM is evidence-based and proven to improve outcomes for the individual such as satisfaction with and adherence to care plans.

Standard 2 describes how sharing the decision making is important for building a care plan. This toolkit This toolkit provides more detail on the 3-talk model that can be used to practice SDM in everyday practice.

Alberta Referral Directory

Alberta Referral Directory to assist with:

- Identifying diagnostic imaging locations

- Orthopaedic surgery referral requirements to the Alberta Hip and Knee Program (if appropriate)

- Designing a local Resource Inventory and keeping it up to date

- Referral to other clinicians

OA Self Management Toolkit

OA Self Management Toolkit, Includes:

OA Self Management Toolkit, Includes:

Self-Management

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive disease with no cure. Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) and Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) findings have concluded that the individual needs to have control of their care journey. The individual lives with their evolving disease every day, while the clinicians only provide support for short periods of time or short interactions1313Not available.. Throughout these nine standards, the principles of self-management are reinforced. Confidence in self-management can be supported by employing ‘family and patient-centred care’ principles using shared decision-making techniques.

All the processes and strategies described in these standards focus on empowering the individual to gain knowledge and to make choices for their OA journey based on that expanding knowledge. The principles of self-management are crucial to day-to-day symptom management. Symptoms of OA can flare up without explanation and the empowered, engaged and educated individual will be able to take action when this occurs.

As care progresses, every clinician should support the individual to gain confidence in applying their expanding OA knowledge to make treatment and self-management choices. Self-management strategies for OA include:

- Priority and goal setting

- Self-evaluation

- Problem-solving

- Mental health management

- Symptom management:

- Thermotherapies

- Activity self-selection

- Seeking clinician appointments as needed

More detail is provided in Standard 7 for those individuals who want to build more confidence in self-management techniques.